Originally published March 22, 1998, by Mike Barnicle for The Boston Globe

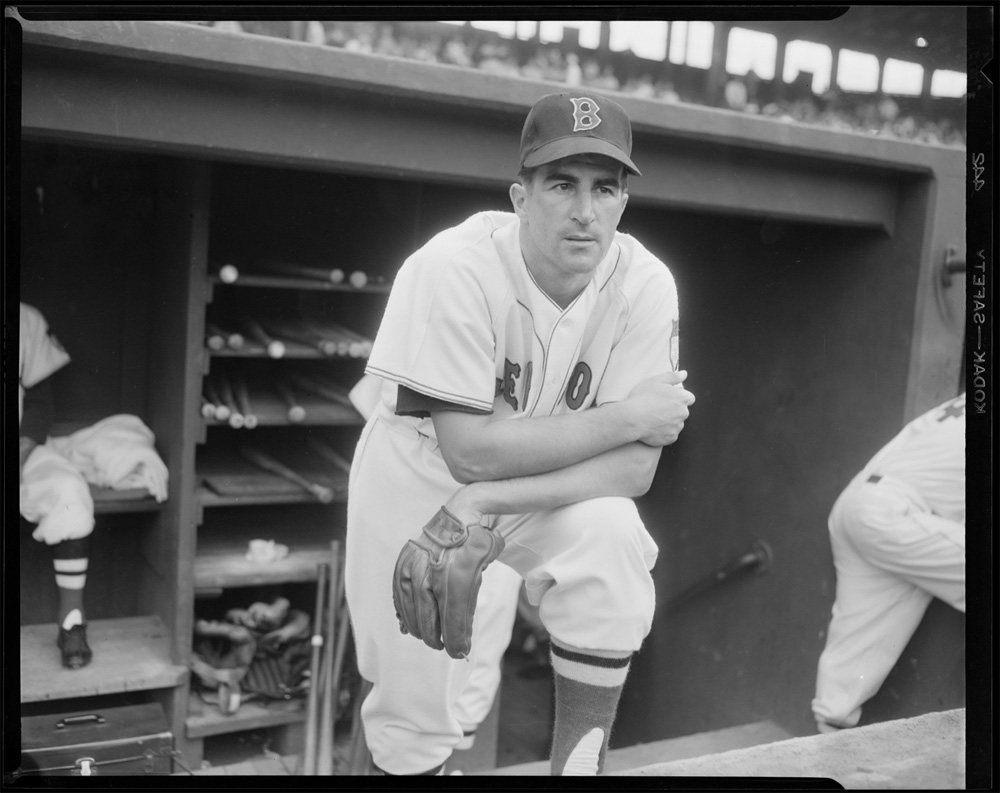

He arrived on the job early the other morning, carrying the same items he’s lugged across more than six decades of employment in a boy’s game: a bat, a ball, and an infectious smile on his 79-year-old face.

“First time I met Ted Williams?” Johnny Pesky said, repeating a question. “1937. I was the clubhouse kid in Portland and Ted was playing for San Diego of the old Pacific Coast League. I was 17. He was 19. We’ve been friends ever since.”

The old man stood in front of his office — a locker filled with a uniform, cigars, T-shirts, and his ever-present work tool, a fungo bat — as he peeled away the years between his major league debut in 1942 and a day last week when he conducted practice for a few children, some younger than Pesky was when he got his first baseball paycheck in 1930 for shining shoes. He was the son of immigrants struggling through the Depression in a country mesmerized by a perfect game.

“My parents were sticklers for discipline,” Pesky was saying. “Other scouts offered more money, but my mother told me, `No. You sign with Boston’ because their scout was very polite. She made a good choice for me. She sent me to heaven.”

Pesky represents a glorious past, the grand history of a great game now threatened by greed, selfishness, and amnesia. Most of today’s players are in uniform for the money, mercenaries with no sense of tradition and even less loyalty.

It is spring 1998, a fantastic time of instant communication and computer magic. Yet, with each new invention and every bold step into the future, we lose a bit of our legacy. In an age of e-mail, digital cell phones, and pagers, fewer communicate by tongue, telling stories that paint a proud picture with details often omitted on the screen of some PC. Stored memory has nearly been eclipsed by electronic skywriting.

“We’re playing the Yankees one day in 1942,” Pesky recalled. “It’s a 1-1 ballgame going into the bottom of the eighth. Spud Chandler’s pitching for them, a mean guy.

“That year, I was nothing-for-16 against Chandler. I mean, I couldn’t hit him to save my life, and I’m up third. Ted comes over to me in the dugout and says, `Listen, you dumb little so-and-so, the reason you can’t hit Chandler is you’re trying to pull the ball on him. I can’t even pull it on him, and look at the difference between you and me: You’re a midget.’

“I come up with two outs,” Pesky continued. “I run the count to one and one, and I see Red Rolfe at third base for the Yanks, he’s way in on the infield. Ted’s in the on-deck circle, and he’s screaming, `Go with the pitch, stupid.’ So I do, and I line a single into left over Rolfe’s head.

“Ted comes up and Chandler is screaming at me; you wouldn’t believe the things he’s calling me. Then he turns and starts pitching to Williams. Well, he grooves one and Ted hits it 30 rows up in the bleachers and he’s taking his sweet time coming around the bases, too. By the time he crosses the plate, I’m already back in the dugout and everybody’s congratulating Ted. I’m sitting there like Joe Nobody when Ted finally comes over with this big grin, and I looked at him and said, `You know, you never even would have got up if I hadn’t gotten my hit, and the only reason you got the pitch you did was because Chandler was so mad at me he forgot about you.’ Boy-oh-boy, let me tell you, that seemed like it all happened yesterday.”

No other game lends itself to stories, to tall tales and true tales, to the very history and social fabric of the country, as much as baseball does. And on a warm Florida morning, standing on emerald grass beneath a blue sky, surrounded by a half-dozen kids eager to shag flies and chase grounders, Johnny Pesky’s recollections assume the gentle tone of a hymn because they are woven by a man filled with a faith so few hold today: a belief in his game and everything it has given him.

“My brother out in Oregon still lives in the same house Mr. Yawkey bought for us in 1942 after I signed with the Boston Red Sox,” Johnny Pesky proudly stated. “The house is near the same church where my father took me to 11 o’clock Mass on the Sunday I returned from the war, wearing my dress whites. He insisted we walk right down the center aisle so all his friends could see me, because he was prouder of the fact that I wore that uniform than any other. Boy, it’s been a great life, I’ll tell you that.”

Then, he grabbed his fungo bat and called to the kids who assembled about him as if he were a Pied Piper in crimson hose. They all knelt on the grass as Johnny Pesky, 79 and younger than most, began telling stories they will never forget about an admirable life and a marvelous game.

###

(Image:Courtesy of the Boston Public Library, Leslie Jones Collection.)