Mike Barnicle discusses A-Rod’s baseball career on MSNBC’s Morning Joe.

Category: Barnicle on Baseball

Mike Barnicle on Pitching Injuries | Morning Joe

Mike Barnicle discusses the science behind pitching injuries on MSNBC’s Morning Joe.

The Glove | Robert Redford Narrates Special | Hollywood Reporter

Robert Redford narrates an excerpt from Mike Barnicle’s “The Glove“, in honor of the 4th of July holiday. The two minute piece honoring the relationship between ball players and their gloves, aired during a double header on July 4, 2014. Making this piece even more special, the piece was produced by Barnicle’s sons, Colin and Nick Barnicle, and colleague Jeff Siegel, of Prospect Productions.

http://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/robert-redford-narrates-fourth-july-716607

Mike Barnicle Talks Baseball | Morning Joe

Mike Barnicle banters with the Morning Joe team about Boston Red Sox spring training during a segment of The Sideline.

Mike Barnicle Commenting on Free Agent Status | Morning Joe

Mike Barnicle discusses free agent status on Morning Joe

Inside Iconic Fenway Park

Mike Barnicle speaks about the magic of Fenway Park, and the iconic stadium’s hold on the people of Boston in “Inside Fenway Park: An Icon at 100 Part II”

THE TENTH INNING | Mike Barnicle: “Don’t lose your stuff” | PBS

Mike Barnicle talks about the baseball gloves he’s had since 1954.

“The Tenth Inning,” is a two-part, four-hour documentary film directed by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick. A new chapter in Burns’s landmark 1994 series, BASEBALL, “The Tenth Inning” tells the tumultuous story of the national pastime from the 1990s to the present day.

A Believer’s Baseball Hymn

Originally published March 22, 1998, by Mike Barnicle for The Boston Globe

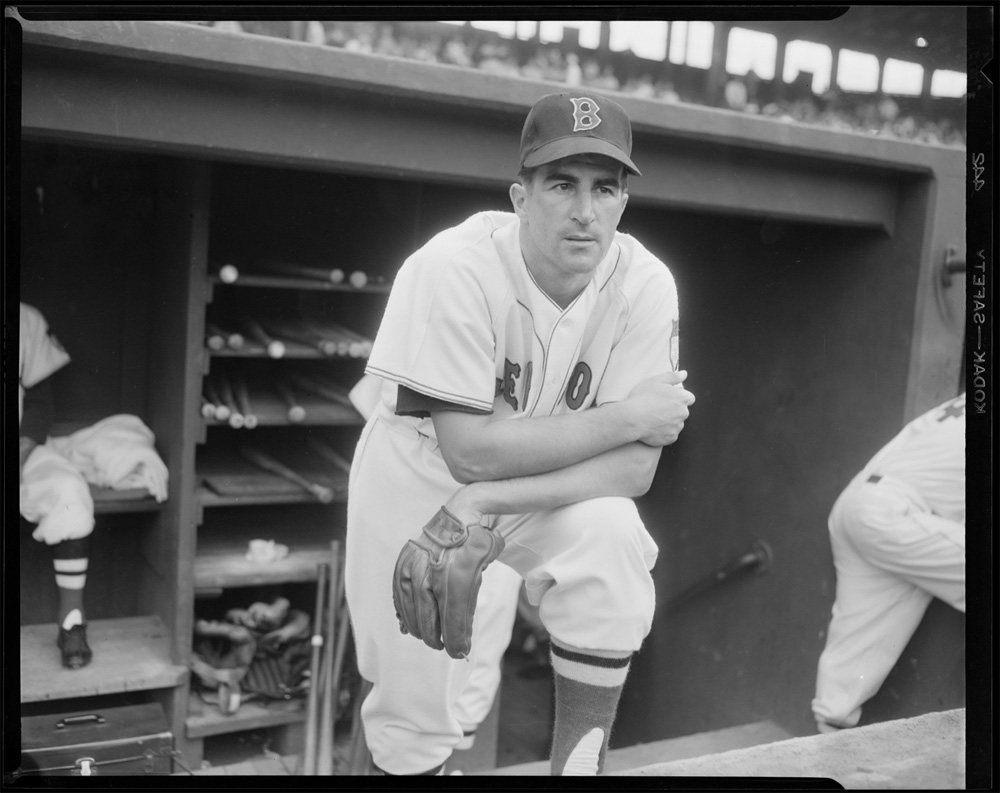

He arrived on the job early the other morning, carrying the same items he’s lugged across more than six decades of employment in a boy’s game: a bat, a ball, and an infectious smile on his 79-year-old face.

“First time I met Ted Williams?” Johnny Pesky said, repeating a question. “1937. I was the clubhouse kid in Portland and Ted was playing for San Diego of the old Pacific Coast League. I was 17. He was 19. We’ve been friends ever since.”

The old man stood in front of his office — a locker filled with a uniform, cigars, T-shirts, and his ever-present work tool, a fungo bat — as he peeled away the years between his major league debut in 1942 and a day last week when he conducted practice for a few children, some younger than Pesky was when he got his first baseball paycheck in 1930 for shining shoes. He was the son of immigrants struggling through the Depression in a country mesmerized by a perfect game.

“My parents were sticklers for discipline,” Pesky was saying. “Other scouts offered more money, but my mother told me, `No. You sign with Boston’ because their scout was very polite. She made a good choice for me. She sent me to heaven.”

Pesky represents a glorious past, the grand history of a great game now threatened by greed, selfishness, and amnesia. Most of today’s players are in uniform for the money, mercenaries with no sense of tradition and even less loyalty.

It is spring 1998, a fantastic time of instant communication and computer magic. Yet, with each new invention and every bold step into the future, we lose a bit of our legacy. In an age of e-mail, digital cell phones, and pagers, fewer communicate by tongue, telling stories that paint a proud picture with details often omitted on the screen of some PC. Stored memory has nearly been eclipsed by electronic skywriting.

“We’re playing the Yankees one day in 1942,” Pesky recalled. “It’s a 1-1 ballgame going into the bottom of the eighth. Spud Chandler’s pitching for them, a mean guy.

“That year, I was nothing-for-16 against Chandler. I mean, I couldn’t hit him to save my life, and I’m up third. Ted comes over to me in the dugout and says, `Listen, you dumb little so-and-so, the reason you can’t hit Chandler is you’re trying to pull the ball on him. I can’t even pull it on him, and look at the difference between you and me: You’re a midget.’

“I come up with two outs,” Pesky continued. “I run the count to one and one, and I see Red Rolfe at third base for the Yanks, he’s way in on the infield. Ted’s in the on-deck circle, and he’s screaming, `Go with the pitch, stupid.’ So I do, and I line a single into left over Rolfe’s head.

“Ted comes up and Chandler is screaming at me; you wouldn’t believe the things he’s calling me. Then he turns and starts pitching to Williams. Well, he grooves one and Ted hits it 30 rows up in the bleachers and he’s taking his sweet time coming around the bases, too. By the time he crosses the plate, I’m already back in the dugout and everybody’s congratulating Ted. I’m sitting there like Joe Nobody when Ted finally comes over with this big grin, and I looked at him and said, `You know, you never even would have got up if I hadn’t gotten my hit, and the only reason you got the pitch you did was because Chandler was so mad at me he forgot about you.’ Boy-oh-boy, let me tell you, that seemed like it all happened yesterday.”

No other game lends itself to stories, to tall tales and true tales, to the very history and social fabric of the country, as much as baseball does. And on a warm Florida morning, standing on emerald grass beneath a blue sky, surrounded by a half-dozen kids eager to shag flies and chase grounders, Johnny Pesky’s recollections assume the gentle tone of a hymn because they are woven by a man filled with a faith so few hold today: a belief in his game and everything it has given him.

“My brother out in Oregon still lives in the same house Mr. Yawkey bought for us in 1942 after I signed with the Boston Red Sox,” Johnny Pesky proudly stated. “The house is near the same church where my father took me to 11 o’clock Mass on the Sunday I returned from the war, wearing my dress whites. He insisted we walk right down the center aisle so all his friends could see me, because he was prouder of the fact that I wore that uniform than any other. Boy, it’s been a great life, I’ll tell you that.”

Then, he grabbed his fungo bat and called to the kids who assembled about him as if he were a Pied Piper in crimson hose. They all knelt on the grass as Johnny Pesky, 79 and younger than most, began telling stories they will never forget about an admirable life and a marvelous game.

###

(Image:Courtesy of the Boston Public Library, Leslie Jones Collection.)

Baseball’s Timeless Beauty

“…your baseball glove. It’s got a soul, a memory all its own, and a future that never fades because it has never let go of the grasp the past has on you and so many others.”

Extract taken from Mike Barnicle’s “The Timeless Beauty of Baseball.”

THIS COULD BE THE WEEK FOR A SOX TITLE

Originally published April 4, 1980, by Mike Barnicle for The Boston Globe

The Red Sox, behind the 32hit pitching of Mike Torrez and the hot bat of Stan Papi, clinched the 1980 American League East title yesterday before a crowd of 612 fans at Fenway Park. The 1914 victory over the Detroit Tigers enabled the team to finish the strike shortened season with a record of 12 wins and 4 losses, resulting in Boston’s first division title since 1975.

“You can name a lot of guys responsible for this thing,” Tommy Harper, the Red Sox manager, said. “But in the end, it came down to one thing, one big thing: the season was too short for us to choke.”

Harper, the first Red Sox manager to weigh less than 150 lbs., is a strong contender for American League Manager of the Year award. He assumed the job during the Patriots Day All Star break when Don Zimmer was fired after the team lost two straight games.

“I don’t want to knock anyone who came before me,” Harper was saying yesterday. “But this club would have done a lot better through the years if there was no September.

“These kids were always under a lot of pressure in September. You could see it in their throats,” Harper said. “Now with this new schedule, you start on April 14 and finish on May 23. A club like this one has a great chance with something like that. We always get off to a fast start. Thank goodness for the Players’ Association: they’re responsible for this pennant.

“I am sorry for a guy like Yaz though. He might retire and if we had played a full season, he was going to get a boat in Minneapolis and a car in California when they had days for him there. Now he gets nothing and that’s not what this game is all about.

“We had a great season though,” the manager said. “Injuries weren’t a factor except for Eckersley’s constant nose cold. We got a couple breaks in the schedule. And we got hot at just the right time when we reeled off those three straight wins against Toronto.”

“I’m sorry to see the year come to an end,” Red Sox Captain Carl Yastrzemski said. “I’m going to miss all that meal money that management would have to have given us if we played the full season.

Torrez, the hardthrowing righthander, came through with his third victory of the season against the young Tiger team. Luck was on the side of the Sox however as the game was completed in less than 180 minutes. Torrez, under his contract, does not have to work more than a three hour day.

“Where’s my free beer?” the ace of the staff was yelling in the middle of the clubhouse celebration. “Next to your free shoes,” it was pointed out.

“What free shoes?” Jim Rice demanded. “Torrez gets free shoes and I don’t? What’s going on here anyways?”

The game was nearly lost in the bottom of the seventh inning. Burleson led off with a sharp single to left. After Jerry Remy flied out to deep left field, Fred Lynn doubled to right, scoring Burleson and tying the score at 10.

Rice then lashed a line drive single to right. Lynn stopped at third despite being waved home by third base coach Eddie Yost.

“Under my contract, I don’t have to run hard until after June 15th,” Lynn explained later. “If I do put out before then, the club has to reimburse me if I sweat or if I breathe hard.”

Lynn scored when the next batter, Carlton Fisk, hit a one handed fly to Tiger centerfielder Kirk Gibson. The rookie outfielder was busy at the time working out an agreement for a series of beer commercials and the ball skipped past him all the way to the edge of the cinder track.

“Those are the breaks,” Gibson’s lawyer said. “He’s upset about that but the commercials are a great opportunity for him.”

“Gibson’s going to be a great one,” Tiger manager Sparky Anderson said. “The kid can do everything: TV, radio, print ads, everything.”

“It’s been a long, long year,”said Steve Renko. “I’m sure that most of the players are sorry to see the season end though because it’s been a great one.

“It’ll give us a lot of things to look back on while we’re home striking this summer. A lot of pleasant memories.”

Renko, who hurled four complete innings over the course of the 1980 season, pointed out that the players did not really want to walk out. “It was forced on us,” the pitcher said.

He pointed out that the average salary for a major league ballplayer in 1979 was only $113,000. In addition to this, management now wants the right to be compensated for players who leave a team for more money elsewhere.

“The owners just want to make baseball like all the other pro sports,” Renko said. “Just because basketball and football and hockey all have compensation doesn’t mean we should have it. Baseball players are different.”

Outside the ballpark, 12 fans stood in the darkness, celebrating the title. Inside the clubhouse, the ballplayers were putting slugs in the pay phone as they tried to find a restaurant owner willing to pick up the tab for a victory celebration. They all wanted to go someplace where no tipping was allowed.

###